Read our interview about BankersLab’s Experimental Design Simulation Courses

BankersLab CEO and Co-Founder, Michelle Katics, sat down with Uli Zeisluft, BankersLab Faculty, to discuss one of the hottest trends in Fintech, Experimental Design. Our simulations allow Bankers and Lenders to design and test thought experiments in our virtual lending lab.

Michelle: How would you describe the concept of experimental design?

Uli: Experimental design is more of a life skill than anything else, and we often intuitively do it. Our industry needs to be more aware of it and to apply it more intentionally. As the name discloses, at the core of it, our experiments are supposed to be employed to try to figure out if you know something is working or why something isn’t working. You can actually use that approach to make an informed decision about a change that you feel like you want to or need to introduce, or you just prepare yourself for a particular eventuality. It puts you into a more informed driver’s seat and you’re not getting caught off guard when something changes that you haven’t perceived before.

Michelle: Do you feel like there’s a more dynamic environment out there at the moment for lending that’s causing the interest in the topic?

In our industry, the time gaps are getting shorter and shorter. There’s more change coming from a variety of places, and it’s always a combination of technology on one side that could either be a threat or an opportunity. At the same time, we have the availability of new data sources. These new data sources that have previously been untapped come with the potential to really open a new universe of insights.

Michelle: It sounds like in the experimental design you’re talking about, you also get some answers as to why and how and root cause and sort of the drivers behind it. It’s not just about the result, is it?

The important part is to identify and understand cause and effect. If I change this element, what is the outcome? What does it mean for my business? Can I be proactive about it? Can I experiment with this? Can I set up scenarios that allow me to play this through and simulate it so that if it happens, I’m better prepared? It’s relevant to anticipate changes ranging from catastrophic, to something that is simply a new opportunity. Also, if I have an idea to change a strategy, it’s easy to test it first.

It would be careless just to deploy something that hasn’t really been tested, which is why in particular experimental design is such a useful approach to identify what we’re doing right, or what happens if we change something. You know what is the impact on that? More importantly, we can test it out on segments and sub segments.

Michelle: Customers are dynamic. Their preferences and motivations change over time. Just because you did something last year and it worked, that doesn’t mean it’s going to work this year, so you have to keep testing. If you just keep doing what you did five years ago, that’s probably not going to work.

You are absolutely right! This reminds me of a favorite pastime of mine – sailing. Let’s say that we want to go to the lighthouse on the other side of the lake. I am exposed to so many variables that I’m either in control of or not in control of, such as currents, and boat traffic. Maybe I’m distracted and I encounter a sandbank. I quickly change and adjust my path. This is really what adaptive control is all about, right? I realize that within a changing environment there are different ways of getting from A to B, but I have to become very conscious of how I get there.

Michelle: We’ve seen too many lenders set up a strategy, and it’s working initially so they just let it run. There should be a constant cycle of tests and learning for so many decision areas.

Uli: When a problem, challenge or opportunity has been identified, the first step is to formulate a “what if” hypothesis. Let’s say I want to outsource my early stage collections activity to a white label collection service provider who can take advantage of large databases and sophisticated artificial intelligence. Technology will probably go beyond what I’ve been able to establish as my core competency. What if I were to do this for a particular subset of my population? I can run a test to determine if I should roll this out more broadly.

Michelle: At the sub segment level it’s a whole set of tests. it’s not like you have one big pot on the burner and you’re just watching it boil. If you’re doing experimental design, you have many pots on the burner with various tests in various decision areas, and each one would have different little tests under the hood for different segments. Isn’t it?

Uli: Absolutely! Our workshops are designed in a fashion that we’re taking some real life examples to make it more tangible and relatable. For example we discuss the hypothesis that using our phones just before we go to bed has a negative impact on the quality of our sleep. Once people go into that exercise, they realize how challenging, but also how exciting it is to understand how you define the experiment. For example, do you perform the test with a group of test candidates when they are at home or would you take them to a different environment like a sleep lab or a hotel? What if you put them into a different bed and they can’t sleep well because that’s not there? How do you make sure to create an experiment that isolates the variables of interest, and how should you measure the outcome? We want the test results to be valid and replicable.

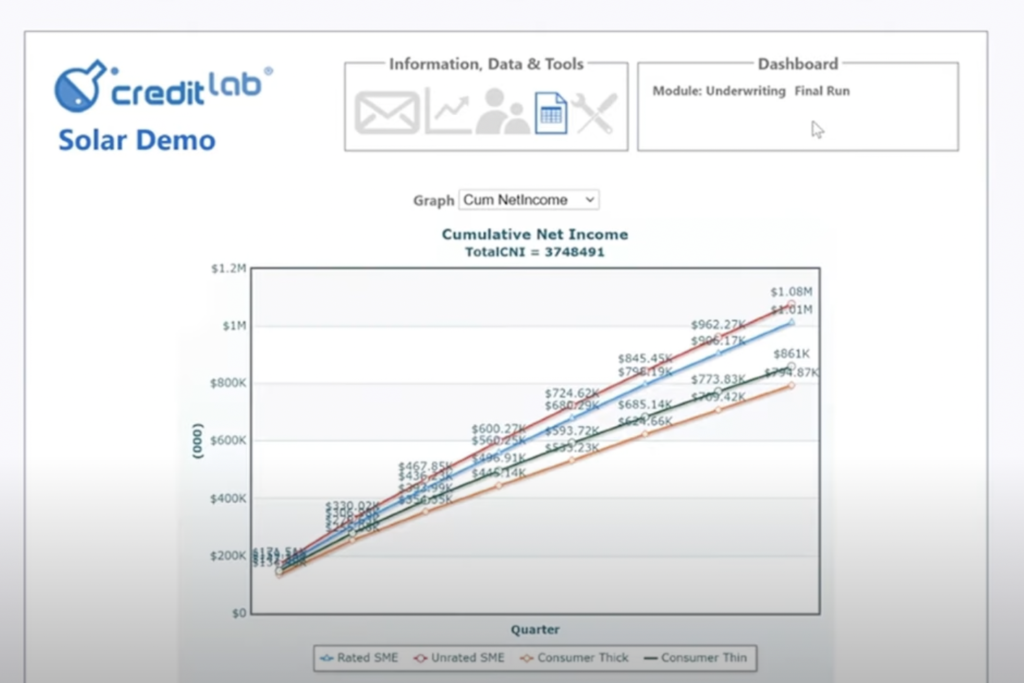

Michelle: Exactly, and then with test results you can extrapolate. For example, we had 15% benefit from a test strategy. If we multiply out, that means that it’s worthwhile for us to invest XYZ to fully roll out the strategy. What did you enjoy about running this particular workshop?

Uli: In every workshop I really enjoy seeing the evolution of the participants in terms of how they formulate their ideas. There are expectations, and then over the course of the workshop, people drop the reservations they might have had and open their minds.

CollectionLab: An overview of results from a test run of our CollectionLab Simulation

Michelle: So Uli, you also teach courses on topics such as underwriting collections, data storytelling. You continue to mention just now about how you link these topics. How did your mind connect to the other topics, such as underwriting collections, data, storytelling, etc.?

Uli: I would group these workshops into two very broad categories. First there are the ‘hard skills’. For example, those we teach in our underwriting, or policy setting or collections workshop. In those subject matter expertise courses, I am sharing the nomenclature, and building the knowledge base so that participants can practice their skills in a simulation so that they become even better at their job or be retrained for a new job.

Although scientifically grounded, experimental design is a broad skill, and in some ways, a soft skill. Experimental design and data storytelling fall into the same realm: they allow us to take a step back and be methodical about how to approach, solve and explain a problem. Before I take action, I stop and think, ‘what am I actually doing here’? The experimental design process is the delivery of that experiment. The results encapsulate the insights, and now, how do I translate this into a clear and compelling story that allows everyone to come to the same understanding. At the end of the day, humans will review those results and insights and make decisions, so it’s our responsibility to clearly explain the results.

Michelle: So, if you learn all of the technical stuff, you’ll understand the movements in the portfolio. But at the end of the day, what are you delivering with those hard skills? You should be delivering actionable insights. And if you don’t have both experimental design and data storytelling you won’t be able to do that. So it seems like experimental design and data storytelling are actually the last mile of how you apply your knowledge of those hard skills.

Uli: Otherwise you would be experimenting into an empty space, right? So if you’re a mechanic adjusting the jetting of an engine, you need to know if the engine will be used in the desert, at sea level, or high altitude. These are very different environments and unless you really understand to ask the right questions before and prepare yourself, you won’t deliver the right solution. In this case, the hard skills might be performed excellently, but for the wrong reasons.

Michelle: So let’s say that you were an experienced banker. You’ve been in the industry for decades, so you have strong subject matter expertise in lending. How would it help you to learn more about experimental design?

Uli: I think we sometimes underestimate people who have reached a certain level of seniority in their company. They’ve gone through a lot and they’ve acquired that subject matter expertise not overnight, but at the price of painful experiences and some mistakes along the way. Over time they figure out how to make these decisions. And, the higher up you are in the organization, the greater the impact of a decision – so you cannot afford to make such a decision without the necessary information to substantiate it. One of the benefits for seasoned individuals to join one of those workshops is to be with people from different parts of the organization. This results in a creative environment where we can take advantage of industry experience that maybe exceeds your own. Or, you might tap into somebody who just finished university and has some really interesting new ideas.

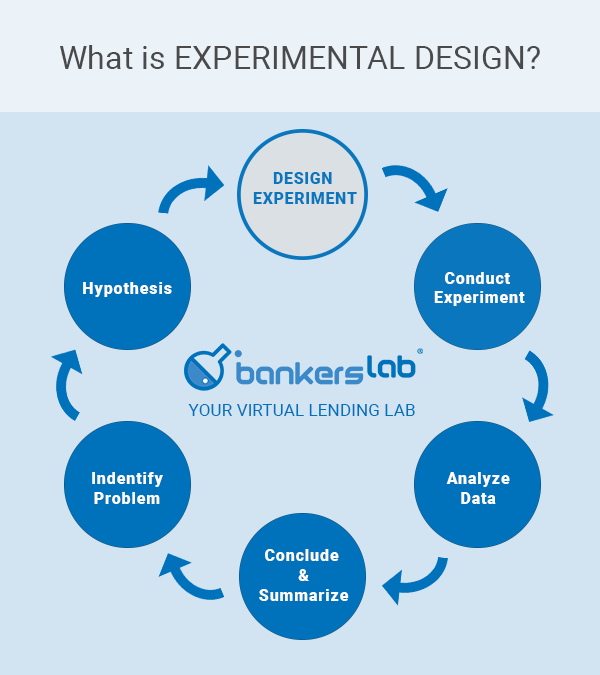

In a simulation workshop, you can do this in an environment where there’s no consequence from a poor outcome. It doesn’t end with attending the workshop, this should be the beginning. Now you can go back to real life and formulate the hypothesis. You gather the right people. You design the experiment. You conduct the experiment. You analyze the data and conclude the results, and prepare the results in a compelling fashion.

Michelle: I expect it’s fun at the end of the course when you have a friendly competition to see which team wins and get the competitive spirit going for those final team results?

Uli: Yeah, absolutely. We’re trying to create an environment where it doesn’t really matter what you do for the organization. I think everybody gains an appreciation for how valuable each individual contribution is. Our simulation is a complex representation of lending portfolios, in which everybody in the organization plays a part in management. As a result, we see teamwork across departments and levels of seniority. In our worksop, we have the opportunity to really see that collaboration in the team breakout rooms. I particularly enjoy the gamification of the experience. We let people present their results and the other teams become the judges. Teams assign an appreciation score, recognizing how well the team has done and it’s beautiful to see how this translates into a recognition for another team’s effort.

Michelle: The cross-pollination of all those ideas across business units is very powerful.

Uli: This could potentially lead to a different type of culture. That’s why I really believe that the organizations who are able to not just withstand the perceived threat from somebody on the outside, but actually internalize it and become part of that change, or even become agents of that very change will do very well.

Michelle: Good! I hope you’ll be teaching many more of these in 2022, Uli.

Uli: I am almost certain of that.

Terms and Definitions for Experimental Design

Adaptive Control: A form of control system whose parameters may be changed dynamically in order to adapt to a changing environment.

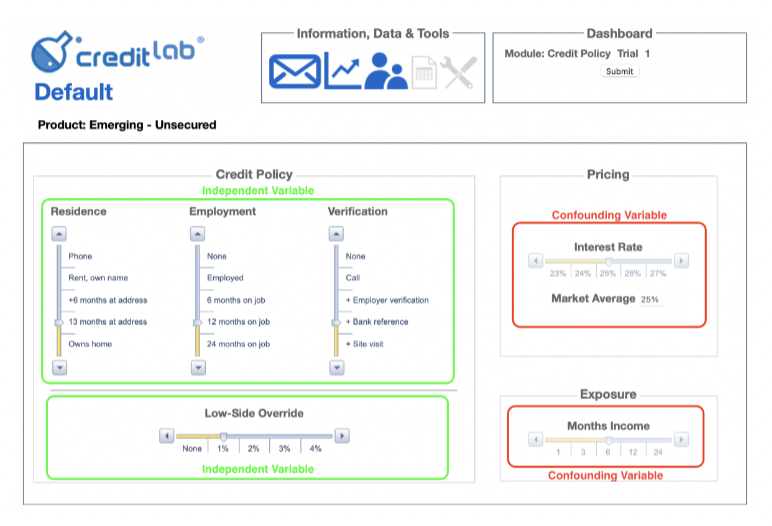

Confounding Variable: A particular error variable whose possible effects on the dependent variable are completely consistent with the effects of the independent variable. The presence of a confounding variable precludes being able to ascribe the changes in the dependent variable exclusively to the independent variable. The changes could also be due to the confounding variable. Confounding variables must be controlled for, for example, through randomization or by holding them constant.

Control Variable: One can prevent the effects of a specific, identifiable error variable from clouding the results of an experiment by holding this error variable constant. For example, if all subjects are the same age, then variations in age cannot act as an error variable. A variable that is thus held constant is called a control variable (Of course one can then no longer generalize the results to those of ages other than the age selected for the experiment).

Cross-pollination: Just as in the plant world, where new life arises from the introduction of pollen from other plants, all great ideas arise from combinations of ideas that haven’t met yet. In both cases, we call this process cross pollination. You get a greater diversity of ideas by collaborating with a greater diversity of creative people—people from a variety of disciplines, departments, cultures, ages, mindsets, motivations, and orientations.

Dependent Variable: A dependent variable is a factor that may change as a result of changes in the independent variable. It is the “outcome” or “effect” variable, usually a measure of the subjects’ performance resulting from changes in the independent variable.

Experiment: In an experiment, the experimenter deliberately manipulates one or more variables (factors) in order to determine the effect of this manipulation on another variable (or variables). An example might be measuring the effect of noise level on subjects’ memorization performance of a list of standard nonsense syllables (such as ZUP, PID, WUX, etc.).

Eventuality: A possible event or outcome.

Hypothesis: A tentative explanation for a phenomenon, and is used as a basis for further investigation. It is a specific statement of prediction and describes what you expect to happen in a study. An example of an hypothesis might be: “Students study more effectively in quiet than in noisy environments.”

Independent Variable: An independent variable is a factor that is intentionally varied by the experimenter in order to see if it affects the dependent variable. The “treatment” variable that the experimenter hypothesizes “has an effect” on some other variable. (See Dependent Variable, above). In the example above, the independent variable would be the level of noise (in this case with three levels: low, medium, high). In an experiment, the independent variable is directly manipulated by the experimenter.

Population: The group to which the results of an experiment can be generalized.

Replicate: Replicates are individuals or groups that are exposed to the same conditions in an experiment, including the same level of the independent variable. It is necessary to have replicates to prove a relationship between independent and dependent variables.

Sources: University of Toronto & California State University, Northridge